A screengrab from the documentary “Do Not Resist.” (Photo: YouTube)

With the stroke of his pen Monday, President Trump rolled back an Obama-era executive order that restricted the types of military surplus equipment that can be deployed to state and local law enforcement agencies.

The Executive Order on Restoring State, Tribal, and Local Law Enforcement’s Access to Life-Saving Equipment and Resources effectively rescinded President Obama’s Executive Order 13688, and all the recommendations issued therein.

At a speech before the Fraternal Order of Police on Monday, Attorney General Jeff Sessions told officers the president’s order “will ensure that you can get the lifesaving gear that you need to do your job and send a strong message that we will not allow criminal activity, violence, and lawlessness to become a new normal.”

Sessions said the restrictions in Obama’s order went too far. “We will not put superficial concerns above public safety,” he said.

But that doesn’t tell the whole story. What did Obama’s order do? And by extension, what did Trump’s order reverse? And how does the 1033 program work?

The “hand-me-down” program

The Department of Defense’s 1033 program was first enacted in 1997 as part of the National Defense Authorization Act. Other iterations of the program began in the early 1990s. Since then, the DoD has transferred more than $6 billion worth of excess military equipment to more than 8,600 federal, state and local law enforcement agencies across all 50 states and in three U.S. territories, according to government figures.

Under the program, the Defense Logistics Agency — an agency within DoD — oversees the transfer of the surplus items. Government Accountability Office investigators earlier this summer released a report finding that DoD actually sold about $1.2 million worth of equipment to “phony law enforcement.” But the phony agency turned out to be GAO investigators.

The House Armed Services Committee held a hearing in late July to follow up on measures the DLA had taken in the wake of that investigation. Mike Scott, the Deputy Director of Logistics Operations at the DLA, explained what a law enforcement agency needs to do to get equipment.

“All requirements first have to pass through a state coordinator,” Scott said. “They review it also against the size of that force, and the number of items that they are allowed to have. The training for the items, that goes back on the law enforcement community. DoD does not provide the kinda ‘use of’ training for what is issued.”

“Do you require the training though?” asked Maryland Rep. Anthony Brown (D-Md).

“We require that they show, and state, that they’ve done that training,” said Scott.

That’s training for airplanes, helicopters, armored/mine resistant trucks, M16’s, M14’s, 12-gauge shotguns, bayonets, pistols, mine detectors, night-vision sights, infrared magnifiers, mine detecting sets, grenade launchers, and swords — among other items.

By the numbers

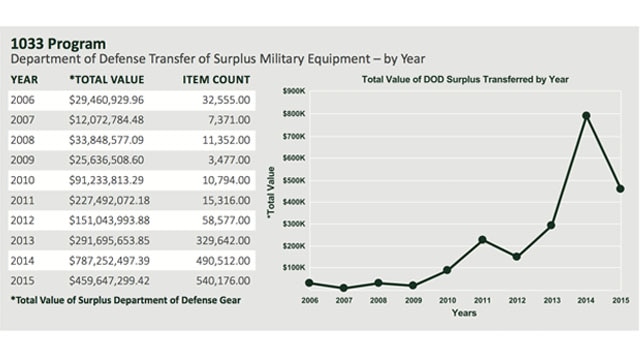

Last year, the transparency group known as “Open the Books” compiled a report analyzing the 1.5 million weapons-related items transferred from the Department of Defense to federal, state, and local law enforcement from 2006 through 2015. The data set included $2.2 billion worth of equipment transfers during that time period.

(Photo: Openthebooks.com)

In 2014 and 2015, the value and number of DoD equipment transferred to local law enforcement peaked. Nearly $800,000 worth of equipment was transferred in 2014. That’s the same year the nation watched as heavily armed police in Ferguson, Missouri used armored vehicles as they clashed with protestors in the wake of the fatal Michael Brown shooting. Those images were part of what led Obama to form a task force and issue his executive order.

“We’ve seen how militarized gear can sometimes give people a feeling like they’re an occupying force, as opposed to a force that’s part of the community that’s protecting them and serving them,” he said in 2015.

Transfers from 2006 to 2015 include: 7,091 trucks worth more than $400 million, 625 mine-resistant vehicles worth more than $421 million, 471 helicopters worth more than $158 million, and 56 airplanes worth more than $270 million.

As for guns, more than 83,000 M16 or M14 rifles (5.56mm and 7.62mm) worth more than $30 million were transferred, as were 8,198 pistols, and 1,385 12-gauge shotguns.

Other weapons included 57 grenade launchers totaling more than $40,000, 5,638 bayonets worth more than $300,000, and 36 swords and scabbards.

The Open the Books agency put together a heat map showing where in the U.S. the items had been deployed from 2006 through 2015. It also allows you to click on the map and see which agencies were issued what.

Obama’s Executive Order

Obama’s executive order created the Law Enforcement Equipment Working Group, which was tasked with developing recommendations to improve federal support of appropriate use and transfer of surplus military equipment. In May 2015, the group offered its final recommendations, and two lists were created: the prohibited equipment list and the controlled equipment list.

Items on the prohibited list could not be purchased by state or local law enforcement using federal funds, and could not be transferred from the DoD. Items on the list included tracked armored vehicles, weaponized aircraft, grenade launchers, firearms and ammo .50-caliber or higher, digital-patterned camouflage, and bayonets.

Items on the controlled list could be bought with federal funds and transferred from DoD, but the agencies were asked to consider the appropriateness of acquiring such equipment. Items on the controlled list included manned aircraft, unmanned aerial vehicles, armored and tactical vehicles, command and control vehicles, firearms and ammo under .50-caliber, explosives and pyrotechnics, breaching apparatuses, riot batons, riot helmets, and riot shields.

In 2016, the government started to recall items from agencies that had received the new prohibited equipment designation.

Trump’s Executive Order

Trump’s executive order undoes all of that, effectively deregulating the process by which law enforcement agencies can acquire military surplus items. Reaction on both sides has been swift.

“This decisive action by President Trump fulfills a promise he made to the FOP during the campaign, and police officers nationwide are grateful to him,” said Fraternal Order of Police President Chuck Canterbury. “The previous administration was more concerned about the image of law enforcement being too ‘militarized’ than they were about our safety.”

“By reinstating this program the President will provide more resources to local law enforcement to keep their communities safe without any additional cost to the tax-payer,” said National Sheriffs’ Association President Harold Eavenson.

But Ed Chung, a former Justice Department official who worked with the group that developed the Obama policy said their efforts weren’t that restrictive. “These weren’t crazy requirements,” he said, adding the Obama order was “about good governance: making sure that people who received equipment through federal programs had common-sense policies in place prior to acquiring them.”

“The prohibited list is a tiny list of equipment that, honestly, when we talked to law enforcement agencies no one could reasonably defend the use of that equipment. Truly no one,” said Roy L. Austin, another former Justice Department official who worked with Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

“What we ran into were sheriffs who said we had no right to monitor what they get or how they use what they get, even though they all acknowledged the fact that this was taxpayer-funded equipment,” Austin said. “All we were asking for was this: Don’t just acquire the equipment and use it willy-nilly. If you’re going to get it, have a reason.”

For Republican Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky), Trump’s order comes down to the size of government. “Americans must never sacrifice their liberty for an illusive and dangerous–or false–security,” he said. “The militarization of our law enforcement is due to an unprecedented expansion of government power in this realm.”

In 2014, Paul grilled a Pentagon official as to why local law enforcement would need bayonets. “What purpose are bayonets being given out for?” he asked Alan Estevez, the principal deputy under secretary of defense for acquisition, technology and logistics.

“Bayonets are available under the program,” Estevez said. “I can’t answer what a local police force would need a bayonet for.”

“I can give you an answer: none,” Paul said.

According to Trump’s plan, bayonets would “likely be re-purposed as utility knives,” according to a report from USA Today.

Ultimately, for the Trump administration, the move to fully restore the 1033 program without any of the Obama-era restrictions “represents a policy shift toward ensuring officers have the tools they need to reduce crime and keep their communities safe,” according to a Justice Department background paper.

“It sends the message that we care more about public safety than about how a piece of equipment looks, especially when that equipment has been shown to reduce crime, reduce complaints against and assaults on police, and makes officers more effective,” the paper says.

The post A closer look at what President Trump’s military surplus executive order does appeared first on Guns.com.